The largest humanitarian group, the Poland-born, totalled 59,441. They mainly arrived as Displaced Persons after World War II.

Berrima

1/27/05

There

was a German camp in the village of Berrima, New South Wales, Australia.

A book has been written on this subject, which is totally fascinating.

The following is a review of the book, which will help you to know

what the camp was about:

World War I brought about some 300 prisoners of war into the tranquil village of Berrima, when the disused sandstone gaol was transferred into a German internment camp. While there were many internment camps located throughout Australia at this time, this book looks at one in particular, brought to life with an excellent photographic collection. Prisoners in Arcady is a fascinating read into years of history into the POW at Berrima

Afforded few comforts, these resourceful seafarers waited out the war far removed from front line action. While confined nightly in cramped cells, they were free to roam by day, "easy-going military guards permitted every liberty that prisoners-of-war could reasonably expect". They bridge the Wingecarribee River, building along its banks chalets and gardens in the style of their homeland.

They supplied fresh produce to a community that learns to accept them, respect them, and even love them with their choir, orchestra and theatre.

It is an incredible story, the photographs I have seen are beautiful. These German people built gorgeous huts on the banks of the river, and paddled around in hand-built canoes. I am just astounded.

For interest - the book is called Prisoners in Arcady: German Mariners in Berrima 1915-1919 by John Simons and is available from The Berrima District Historical Society, PO Box 131, Mittagong, NSW, 2575, Australia. Phone: (02) 48722169. The book costs about $45 plus postage. Regards, Lavinia, e-mail: lavinia@mitmania.net.au

Bonegilla Camp 1947 - 1971 The Migrant Experience

The first migrants arrived at the Bonegilla Migrant Reception centre in the Wodonga district in 1947. Bonegilla is in northern Victoria -- on the border with New South Wales. They had come to Australia under the Commonwealth's Post War Migration Scheme.

The first migrants were displaced persons (DP's) whose lives had been disrupted by the horrors of World War 2. Later migrants were attracted to Australia by immigration advertising in Europe.

Bonegilla was a staging camp, temporary accommodation, for new migrants who had exchanged free or assisted passage to Australia for 2 years of labour at the Australia government's choice. After this service, migrants were free to make their own way.

Bonegilla was the largest centre in Australia. During the 24 years of its operation, 320, 000 people passed through its gates. Persons of diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds, 60,000 of whom were Polish. People came from 31 different ethnic groups. Conditions at Bonegilla were basic with accommodation being in fibro and corrugated iron huts. The food was also basic and, while unfamiliar to many migrants, was typical of Australia.

Oct 12, 2013

Subject: Looking for my Mother

Dear Olga.

Your site has a wealth of information and I am hoping to find answers to my questions. My mother came to Australia in 1950 on board the Nelly out of Bremerhaven. National Archives of Australia have her listed as Imbi Scnuur travelling with Endel Scnuur. This is probably a transcription error as other documents I have list her name as Schnuur. However her real name was Imbi Haabjarv, born Tartu Estonia in 1933. I was born in 1951 and for a short while was called Maria Schnuur before being relinquished for adoption. Any formation would be appreciated. I am hoping, ultimately to make contact with her (is it possible to grieve for someone you have never met) or any other family members.

From the records I have found she arrived in September/October 1950. Might have been Bonegilla camp. She was living in Sydney when I was born. I don't believe Imbi or Endel were married although he was also possibly from Estonia. I do not know why I have his surname not hers. I am awaiting more information from child welfare (handled the adoption) and the hospital. I found a photo of her in 1938 Maret magazine with her name of Imbi Haabjarv. I have found I am grieving for the loss (ie no contact) of somebody I never knew.

All the records are located in Canberra. will be going in a couple of weeks as I work full time (librarian). So am hoping for much more information. This has been an incredible journey for me - although I studied history at university, the experiences of 'ordinary' people was superfically treated, with the exception of the Jewish Holocaust. The enslavement of non-Jewish peoples and Australian attitudes and treatment of DPs who came to Australia is a revelation.

Sincerely Kate Bender kmbender10@gmail.com

Chullora Railway and Migrant Camp

This article

was in the booklet "Canterbury

-- Bankstown "

A railway camp for railway workers was established near the corner of the Hume Highway and Brunker Road, Chullora in 1948. It covered 18 hectares of westerly slopes and initially some 20 huts, called chalets, were constructed. With time 13 chalets covered an area around Anzac Street, North Chullora. Small huts housed single men, larger ones railway staff (drivers, fireman, guards and conductors).

K.T. Groves recorded his memories of the camp. Rent was one pound a week ($2), including electricity (2 ceiling lights and 2 power points). A fuel stove was provided but many residents bought electric stoves. Electricity consumption increased and the railway charged for it. A coal hand-fired vertical boiler shared between a number of chalets provided the only hot water but proved a very inefficient system. Two families shared a laundry (a concrete tub and ironing board). The chalets were hot in summer and cold in winter. For entertainment, there were the local pictures at Bankstown, punchbowl on Saturday nights and soccer matches, which the migrants enjoyed, on Sunday afternoons. The men worked shifts, often 12 hours straight to acquire the Australian dream, their own home. Opposite the workshops at Chullora, blocks of land were selling for 100 pounds in 1950 but it was difficult to save on 8 pounds a week. Working hard, with overtime, Groves and his wife finally purchased a standard block of land at Greenacre in 1955 for 500 pounds.

The Chullora railway camp had an Australian and migrant section. Migrants were generally Eastern European displaced person, mostly Polish. Married men and families were accommodated in cramped quarters. There was a general store, operated by a Polish family. Mc Vicar's buses provided local transport. In 1949, the Catholic Church built St. Francis Cabpini for the Catholic residents at the camp. The church closed in 1965. By 1951 the camp was known as Chullora Accommodation Centre for Migrants. The Sydney Morning Herald ran a 1957 article, "A Shanty Town that makes the Railways Ashamed." Fifteen hundred new Australian men, women and children lived in 40 -3 metres by 2.75 metre huts, which, although bigger were substandard. The one room of the smaller huts served as a kitchen, bedroom, living room and bathroom for a family, often with four children. Life in the huts was primitive. Cooking facilities were provided in a galvanised iron shack with a low roof and cement floor with an open coke and coal fire, burning under two long bars of railway track. There was no running water in the smaller huts, unless tenants had pushed a garden hose through a window. Community showers were galvanised iron sheds with cement floors, hot water piped from a boiler house. Laundries only a trough. Tenants added small vegetable gardens, kitchenettes, carports and fences to some huts. The rent in the migrant section was 1 pound a week . Some of the chalets had additional sleep outs which cost an extra 10 shillings a week. A Polish couple had lived in displaced persons camp in Europe and been housed in notorious Cowra camp for 2 years before arriving to Chullora. Resident five years, they bought a block of land locally and were saving to build a house but declared "it seems we will never have enough." Many mothers worked and the Sisters of Charity had opened an infants school for 120 children. Sister Brendan also ran a club for young girls at the camp.

The Department of Railways regarded Chullora as a temporary measure. There was Housing Commission scheme for provision of cottages of two and three bedrooms of which 80 were erected in Chester Hill and 122 at Lidcombe on railway land. But the scheme ceased because of lack of money. Many of the railway workers purchased land and settled in the district.

A Shanty Town That Makes the Railways Ashamed

Article from the Sydney

Morning Herald - 9th April 1957

In a crowded, run down shanty town at Chullora, 1500 New Australian men, women and children live as tenants of the New South Wales Department of Railways in 640 huts each on 10 feet by 9 feet.

Nearby in 136 bigger huts, Australian workers live in accommodation whilst better than the 10 feet by 9 feet huts is still substandard.

In the smaller huts where one room serves as bedroom, living room, kitchenette and often bathroom, too, New Australians with as many as 4 children live miserably in an atmosphere of hopeless frustration.

Their embarrassed landlord, the NSW Railways, is not proud of the Chullora Camp. To its lasting regret the Department built these huts years ago to house single men coming to work in the city from the country, or arriving from overseas.

But the single men over the years acquired wives and families and now only 140 of the huts house single men. The other 500 huts laid out 15 feet apart in long straight rows are home to some of the unhappiest people in Sydney.

Chullora Park settlement, as it is officially called, is on the Hume Highway, adjoining the railway workshops, an a mile past the much discussed the 102,000 pounds drive in site. A notice warns that the area is railway property and that strangers may not enter without authority.

When I sought permission to inspect the area, the department at first refused, but later the secretary of the department, Mr. W.A. Anderson, gave permission, asking that all the facts which led to the establishment of the settlement be considered.

Old and New

The camp covers 45 acres of westerly slope. Only railway employees can be tenants. The larger huts, officially called chalets, are reserved for running staff drivers, fireman, guards and conductors many of whom have come to Sydney from the country railway centres. Presently, all but one or two

chalets are occupied by Old Australians.

All of the small huts are occupied by New Australians, a division which rankles with the New Australians.

Life in the 10 feet by 9 feet huts is primitive, because the huts when built just after the war, were intended for single men only, the department provided only community showers, toilets and cooking huts. For the mothers of families of small children, they are pitifully crude.

The cooking centres consist of a galvanised iron shack with a low roof and a cement floor. In one, I saw an open coke and coal fire, was burning under two long bars of railway track. A woman, one of a few who have not defied the loosely policed ban on cooking in the huts, was preparing a meal. She had 3saucepans simmering on a sheet of flat tin lying across the bars.

At one end of the bars was a camp oven, which looked as though it had not been used for months. It was the sort of cooking one would have expected in remote fettlers' camp, but not a big city.

Bathing and washing for the inmates of the huts is on the same crude pattern. There is no running water in the smaller huts, except where the enterprising tenants have connected garden hoses through windows. The community showers are in galvanised iron sheds with cement floors. Hot water is piped in from the boiler houses.

The laundries have troughs and wood burning was boilers. Rent of the small huts is 1 pound a week, including electricity. Officially the use of electricity for cooking is banned, because the camp wiring is not designed to handle electric stoves, but in practice only about 50 families use the crude open hearth fires in the community cooking centres. This is just as well, because there is only one fireplace to every 40 huts.

Where a man has more than 2 children, he is supposed to rent 2 huts a 1 pound a week each, but one official admitted that some migrants undoubtedly have understated the number of their children in order to save the cost of an extra hut.

Fifty families rent two adjoining huts, and a few with more than 4 children have 3 huts.

The original 10 by 9 feet boxes have taken on a new shape over the years as Chullora's population had grown from within, tenants have had verandas, kitchenettes, fences to keep the children home and even car shelters.

A year ago, the department doubled the space in one group of huts by moving 2 huts together and making a doorway between them.

The 40 small huts are the worst aspect of the Chullora camp. The 13 chalets though still well below normal housing standard are palaces by comparison and the tenants of the hutments live in constant hope that they may be chosen to make the step up to the chalets.

Pride Shows

A chalet consist of a bedroom, 13 feet by 9 feet, opening into a kitchen, the bedroom has a double bed, a double-tiered bunk for children and ample built-in cupboard and wardrobe space. The kitchenette also has cupboards, a sink with water laid on and a fuel stove.

Pride of possession among the chalet owners shows up in trim lawns, fruit trees, painted fences, polished lino and decorated house names hung outside. I asked the first chalet tenant I saw if he was content with life in the camp.

"I'm very happy," he said. "Anyone who tried to rent a house in Sydney would be glad to live here. I wouldn't care to live in one of the hutments, but this will do me."

Most chalet tenants have contained off the fuel stove and have bought electric stoves. They pay for the current. Half of the chalets have sleep outs, separate huts in the same plot of ground. Rent for the chalets if one pound a week and the sleep out is 10 shillings extra.

But in the hutment section, no one disguised his dislike. I spoke to Mrs S. Maka, whose husband is a fireman and acting engine driver. She came from Poland seven years ago. Like all the New Australians, she had expected Australia to be an Eldorado after the harshness of Europe.

From camps in Europe, she came to Cowra and spent 2 years in a migrant camp there. She has been five years in the 10 by 9 feet hut at Chullora. There are three small children.

The Makas have bought a block of land and have saved some money toward building a house. But as their savings grow, the amount of money they need to start building seems to be growing ahead of them. "It seems we will never have enough."

One of the worst aspects of the Chullora Camp is that there is no where for the large number of children and teenagers to fill in their leisure hours.

Nun's Work

Sister Brenden of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, runs a school

for more than 100 children. "I have another 30 under 3 who come along and watch, although they are to young for school." She said, "A

very big proportion of the mothers go to work and leave the children in the

camp with neighbours or friends. The children have nothing to occupy them,

and many of them drift along to the school."

The schoolroom is a church on Sundays. Sister Brenden, realising the danger to young people spilling out of the overcrowded huts with their appalling lack of privacy, has started a club for young girls in a disused shed, another for boys is being started nearby.

The railways department is well aware that it fathered a monster when it set up Chullora Park Settlement.

The secretary for railways, Mr Anderson said, "The settlement was established for the accommodation of employees transferred from the country to meet the urgent requirements of operating, staff drivers, firemen, guards and shunters, at Enfield locomotive depot and marshalling yards."

It was also for displaced persons brought out by the Commonwealth Government in the International Relief organization scheme and allocated to work with the railway department.

The accommodation was regarded as purely a temporary measure, as the department had in conjunction with the Housing Commission, a scheme for the provision of cottages for those employees and others in the metropolitan area who were living in tents.

Towards the end, 80 cottages each of 2 and 3 bedrooms, were erected in Chester Hill and 12 in Lidcombe on railway land. Because of the serious financial position, it was not possible to proceed any further with the project.

Mr. Anderson said that the accommodation for migrants originally had been provided for men only, because it has been distinctly laid down by Commonwealth immigration authorities that only heads of families would be allotted to the Railways department to work in the metropolitan area. Their families were to be required to remain in the holding centres at Greta, Cowra and Bathurst.

"As may be appreciated," Mr Anderson said, "great difficulty was experienced in attempting to restrain wives joining their husbands, and such a position was reached that it became beyond the control of this departmentand the Commonwealth authorities."

No Alternative

Forcible removal of the families could only be fraught with serious

repercussions and as a matter of fact the immigration people were quite indifferent as to whether the families remained in the holding centres or not.

"There was no alternative, therefore, but for action to be taken by the department to make certain accommodation blocks available for occupation exclusively for family units. It will be realised the problems that were created in attempting to make the necessary bathing and sanitary facilities available for women and children under these conditions.

"Water, sewerage, electric lighting and power are connected throughout the Chullora Park Settlement and while everything possible was done and is being done to provide reasonable living conditions, it was never the intention of the administration that the accommodation should be regarded as other than a purely temporary expedient.

"The department is already committed to very heavy expenditure in the maintenance of the settlement and funds are not available for other than purely essential needs."

Reply to the Article in Letters to the Editor

Makeshift Homes In NSW

Sir, Your Staff Correspondent's article on the appalling housing conditions at Chullora Park Settlement (April 9) will no doubt disturb many readers. What a comment on the housing situation this is!

The separations of parents and children for lack of accommodation is by no means unusual, and the article on the Chullora park Settlement only seems to emphasise the seriousness and urgency of the housing problem in New South Wales.

The

History of Uranquinty Camp

Uranquinty played role in Populate or Perish Policy

Excerpts from: "From Our Past" by Sherry Morris,

The Daily Advertiser Jan 20, 1996

The migrant hostel was established in December 1948 on the site of the former RAAF Air Service Flying School, some 5 Kilometres north west of the township of Uranquinty. During the occupancy through to its closure as a migrant centre in 1952, near 28,000 displaced persons/ refugees migrants passed through the facility, by far the greater majority of these being women and children.

Male migrants were contracted to work on projects at the discretion of the Commonwealth Dept. of Immigration.

As accommodation became available in proximity to where the workers were situated, then the families moved on from the hostel centre, hence the large figure shown as having been housed at Uranquinty in a relatively short period of time.

The NSW Department of Education opened a school for immigrant children. Staff at the centre totalled 100 by April 1949.

The huts were unlined corrugated iron with few provisions for comfort -- suitable for toughness-building austerity in single men, but not suitable for women, children and particular young babies. Accommodation was dormitory-style for up to 22 people in separate single or family blocks. Though expected to be temporary, the immigrants were often kept there for up to three years.

The residents did their best with improvisation and ingenuity, for example, draping suitcases with material to use as a lounge chair and fastening a long thin metal pipe to a block of wood to make a lamp stand. However, it was still uncomfortable, the flimsy partitions, and the reverberations of the iron roofs meant that all noise including arguments and crying children was amplified. The immigrants thought that the Australian diet was monotonousand when they complained, they were told that if they wanted to live in Australia, they should get used to Australian food.

Because the immigrants were from various European countries, many encountered language problems. One of the main forms of entertainment was the picture show once a week at the cinema hall. There were night classes in English for the adults, and there was a small reference library.

Anne Ringwood, Daily Advertiser reporter inspected the camp after the first arrivals. She noticed the old main gate of the camp chained and locked fast beside a weathered leaning sentry box. The gate was hitched with a wire loop and the notice on the gate pleaded, "Please shut the gate - sheep here." The old parade ground was bleached dry instead of the green the troops were used to. She noticed the strong, friendly-looking women who, she claimed. "looked like pictures in a travel magazine with their bright peasant scarves." The women were standing by in the shade of the huts or were superintending the disposal of their luggage--all their worldly goods in great boxes and blanket bound bales which lay haphazardly on the road way between the huts. The experience must have been very confusing. They had been brought to Australia expecting to regain their freedom and move to wide open spaces, but they were once again herded into camps.

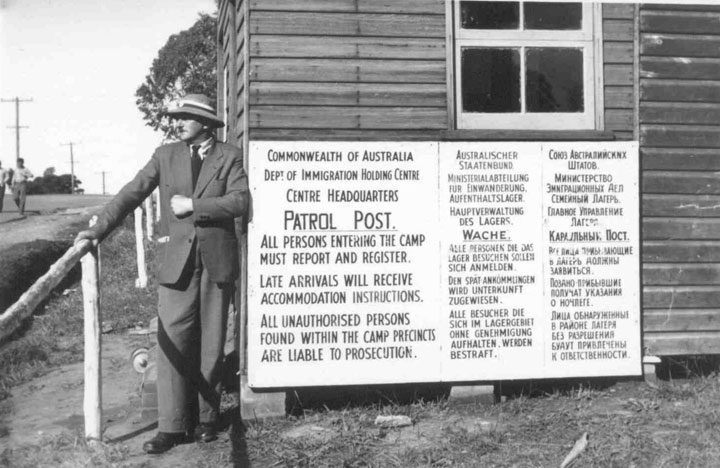

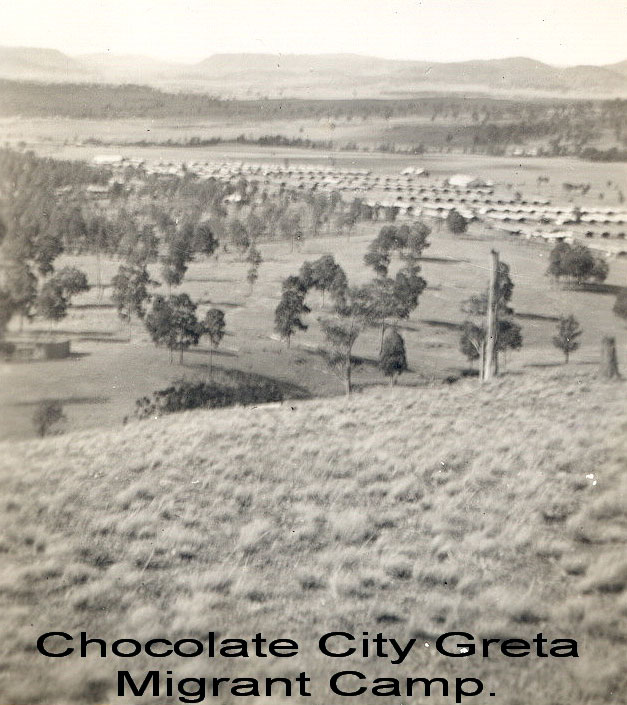

Greta Migrant Camp 1949 - 1960

"The Tale

of Two Cities"

Australia's post-war immigrants scheme had an effect on Australia Society and on National Development. Greta Migrant Camp played a major part in this scheme as it was one of the largest camps in Australia.

The camp was located about 3 klms from the township of Greta. It was built for the Australian Army in 1939. The army occupied the site until early 1949 when Australia's agreement with the International Refugee organization (IRO) to bring Displaced Persons from Europe, was put into action.

The army barrack style buildings were promptly altered to accommodate migrants. The camp was ready to receive the first draft of migrants in June 1949.

It is estimated that some 100,000 migrants passed through the camp between 1949 and 1960. The largest number of people at the camp at one time was in 1950, when some 9,000 people gathered for Christmas.

A change in Australia's Migrant Policy in 1955 saw the camp slowly close from 1956. The camp officially closed on 15th January 1960.

Most of the IRO migrants came from the Baltic countries (of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia), Ukraine, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. During the 1950s, agreements were signed with other European nations. There were intakes from Poland, Italy, Greece, Macedonia, Hungry, Austria, Germany and Russia. Passage to Australia was free for migrants. However, men were required to fulfill a 2-year contract once they arrived in Australia.

The first 600 migrants to inhabit Greta were from other Australia migrant camps. They were soon joined by a large group of new arrivals on board the "Fairsea". These migrants were the first draft of Displaced Persons to be landed outside a capital city. 1096 migrants disembarked at Newcastle harbour on the 19th August 1949 and were transported directly to Greta Migrant Camp by steam train.

These migrants suffered hardships before they arrived in our country and the shock of arriving at a camp in the middle of nowhere, at most times in the heat of summer when everything was brown. The accommodation was basic -- huts had no lining, no heating in winter and no internal doors to connect the rooms. Living in the camp was also not easy for most families. Mothers and children lived in Great Camp while their husbands and fathers worked away, in Sydney, Cairns, and the Snowy River. The luckier families had fathers who worked at BHP and came home weekends. Mostly people socialised even though they came from different nationalities and different backgrounds. They were happy. There was plenty food and lots of space for the children to play.

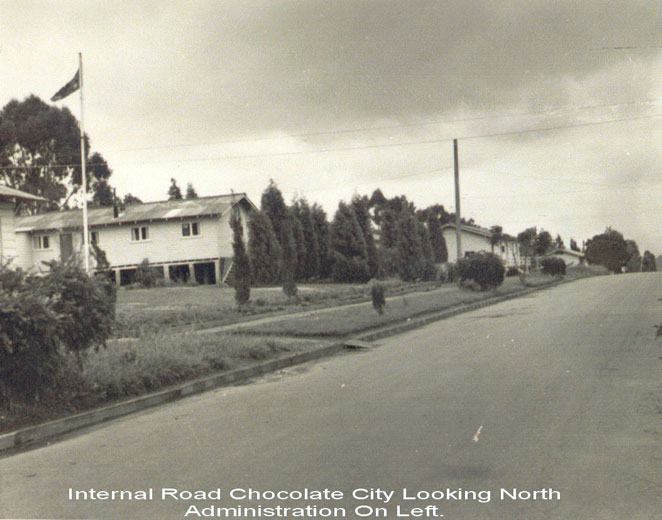

The camp was divided into two separate sections: Silver City and Chocolate City. Silver City was so named because of the galvanised iron sheeting used in the construction of its huts and the brown coloured oiled timber clad huts in Chocolate City which nestled at the foot of Mount Molly Morgan.

Both camps were administered separately with a director or commander at the top and several government executives or assistants. Teachers were provided by the Education Department and an Employment office was opened. The bunk huts measured 20 metres by meters and were divided into ten units, each fitted with a door and lined with thin masonite. Both camps were run along army lines by army men and names such as mess and recreation hall were used. Both Silver City and Chocolate City had their own school, cinema, canteen and chapels. The main hospital was in Silver City. This was one of the largest migrant camps in Australia with a population made up of many nations. At one stage there were 17 different nationalities at the camp. The rental charged at the camp initially was 35 shillings per week for adults and twelve shillings and sixpence for children.

Some excerpts from a story written by Janina Sulikowska for the bi-centennial celebration 20 /8 /1988, "Greta the Camp revisited."

9/23/07

Dear Olga

Sadly

as most people on your site, I also found info after my mother passed

away. She

never spoke of her life at all not even about her parents. If I asked

questions, she would become angry. I am still going through her immigration

files. I was born in GRETA CAMP in 1953 and still live

close to it, so know about the camp.

My mother's files have a lot of info about her life though war years and after but none of the dp camps or work camps are in your site except Bremerhaven and Greta. I did however track down POLISH CAMP LIBERTY Lebach Saar but cannot find any more info. I have photos of people in the camp that I would say were close to Mum. The back of a photo has been stamped with the photographer's name and Lebach saar. Mum was married there in 1945. My older sister was born there in 1946. She then went to NEIDERLAHNSTEIN KOBLENZ 1947. Could you please give more info on these places. I will be also looking for my grandparents' details as soon as I have mum's files translated from German. I also have photos of GRETA CAMP. Looking forward to hearing from anyone who has information on these camps.

Regards, Liz McKenzie, lizzie.mick@bigpond.com, NSW AustraliaFollow-ups:

May 28, 08 Olga you did mention before you would like to start something with the Greta camp site, I would be very interested in helping, https://www.cessnock.nsw.gov.au is where immigration selection files can be requested. might help people if posted in the Greta camp site.

I have learnt a great deal from when I first emailed you Olga (still along way to go) but sadly still haven't found what happened to my grandparents. My mother was born in Poltawa Russia (Poltava Ukraine) and I am waiting for her birth certificate or any information (fingers crossed); very hard to look for information as I do not understand the culture or language of this country.

Regards Liz. Australia. lizzie.mick@bigpond.com10/16/11 Hi Olga,

Today I am sending some photos of Greta Camp. My search for my mother's birth place still continues but I will not give up!! with warm regardsLiz lizzie.mick@bigpond.com

NSW AUSTRALIA.

Main gate Greta Migrant Camp

Internal Road in Chocolate City looking North

Administration on left.

Maribyrnong migrant camp

Mildura Holding camp

Hi,

I am

researching my family history and my family were displaced persons from

Europe. My parents arrived at Station Pier in 1950

in Melbourne. They then went onto Bonegilla and my mother was sent to

the Mildura Holding Hostel. She was pregnant with me at the

time and latter was sent to the Broadmeadows Hostel.

Her name was FRIEDA MOCIAK.

I am trying to learn about the MILDURA

HOLDING CAMP. Are their any records of ARRIVALS or DEPARTURES? Where was

the camp located? Does the site still exist today ? Are their any historical

documents?

Best Regards, Karl Mociak

+61 (0) 417 600 684

k_mociak@bigpond.net.au

Stewart

Could you tell me if you have had any information about a displace persons holding camp called STEWART in Queensland.

We were living there in 1950. I have been unable to find any information about it.

We came to Australia on the Amarapoora and landed in Newcastle on 24 April 1950 Our family name is Blocki

zofia.low@gmail.com